Growing up in rural Lancaster County in the 1950s, I had very little opportunity to meet people of other ethnic groups, but I did have a Little Black Sambo book that introduced me to a culture different from mine. So, I have not always been embarrassed by this book. Fascinated, yes, but embarrassed, no. The picture of the tiger running around an African palm tree as the tiger morphed into a golden round pool of butter mesmerized me as a child, butter that would become one of the ingredients of the pancake recipe. The next page shows Black Sambo’s mother Black Mumbo with her glossy brown arm stirring a mound of melted butter making pancakes. The picture made me hungry. And on the last page:

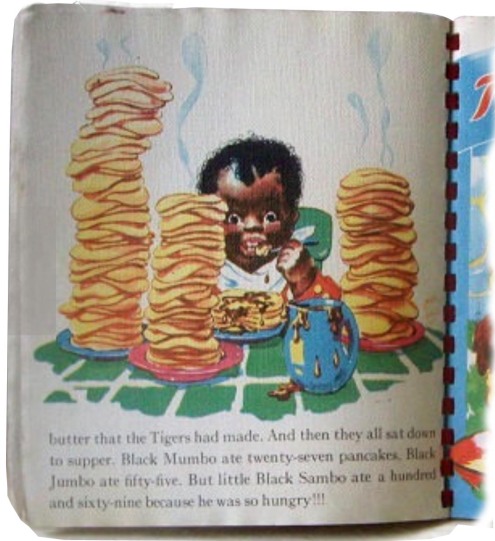

And then they all sat down to supper. Black Mumbo ate twenty-seven pancakes, Black Jumbo ate fifty-five. But little Black Sambo ate a hundred and sixty-nine because he was so hungry!!! (Yes, there are three exclamation marks in the book I am holding.)

Characters in folktales are typically overblown, with exaggerated details like Little Black Sambo’s super big eyes, through which he gazes at three heaping plates of pancakes with a pot of syrup dribbling all over the table. Obviously, he is ready to stuff his mouth with piles of pancakes.

But there are other tales in the book with the Little Black Sambo cover: The Little Red Hen, The Tale of Peter Rabbit, and The Country Mouse and The Town Mouse. Mr. McGregor and the kitchen maid in the “Mouse” story have white faces, but there is no reference to their whiteness. Their race is assumed as white and therefore not particularly notable.

I paged through this book recently as we cleared out books in Mother’s house and marveled at the stereotypes about black people back then and was embarrassed by it: A black woman with a big butt and goofy name wearing a “maid” cap on her head, black people eating nothing but fried foods, everyone eating too much.

Another find un-earthed in our sifting through “Stuff” – a pair of book-ends I made in school that portrays black children as a novelty.

Interestingly, my niece Shakeeta, my brother Mark’s daughter, choose these as one of the few things she wanted as a remembrance from her Grandma Longenecker’s house. She hoists them up with a smile here:

I guess it’s time I catch up with the times and adjust my ideas about black memorabilia. Singer Anita Pointer certainly has. In an article entitled “A Lesson in History,” (AARP Feb/March 2015) Anita, one of the Pointer Sisters, says she collects black memorabilia so she’ll never forget how her people were once depicted.

We grew up in Oakland, California, but when I was 10 we visited my grandma in Arkansas. I couldn’t believe how people were living there. They had a white and a black part of town, and you stayed off the white side. At the department store, they had colored and white water fountains. I don’t want to ever forget that’s what it was like for us — and collecting black memorabilia is how I do that. (66)

Like Whoopi Goldberg and Spike Lee, Anita collects black memorabilia as museum pieces including a “Mammy” cookie jar, and a 1970s John Henry whiskey decanter made by Jim Beam. When the prestigious house of Sotheby’s came to appraise her collection, it took a year to sort and categorize it. She comments, “The appraiser said that I could pretty much charge what I want because most of the pieces are one of a kind.” In the end, Anita Pointer sees her collection of thousands of pieces as part of her personal history. She doesn’t apologize for any of it.

Of course, I’m hanging onto my Little Black Sambo book. It’s a part of my personal history.

Your comments welcome here!

(Answers to Shakespeare puzzlers from April 22, 2015 post below.)