Little Mennonite girls could be fancy before they became plain. They could wear hats. Their mothers may have worn flat, black bonnets on top of their prayer veilings (coverings) at Easter, but they couldn’t wear hats with ribbons and flowers. At least not in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania in the 1950s.

My sisters and I are standing here in front of peony bushes wearing some cast-off hats Grandma Longenecker’s friend, Mame Goss, brought from a millinery shop in Middletown, Pennsylvania.

I recall this scene through the lens of memory:

I’m looking now at a snapshot my mother took of my sisters and me in these hats, the three of us holding hands in front of a peony bed. The magenta peonies are in bloom, so it must have been May. The double whites mingled among them have ruby flecks in their ruffled centers. My sister Janice, three years younger, is standing at one end, with blonde hair fluffed into curls, hands obediently at her side. Jeanie, a tiny tot of two or three, appears to be looking down at the grass, her burst of tulle brushing light brown hair. I’m staring straight at the camera, two thick braids trailing down my back. Our dresses are all bedecked with ruffles and bows, embroidery or smocking, dresses surely made by our plain Mennonite mother.

I wore my first adult hat ever, a pale blue clôche with a blue chiffon dress one spring when Cliff and I were dating.

At Crista’s 5th birthday party I was wearing a knitted skull-tight cap, typical of the 1970s.

In the 1990s I bought a white hat trimmed in black ribbon and feathers, probably for Easter. I don’t wear hats anymore. I have already taken this one to Angel Aid, a charity for mothers and children.

My sister Jan and I wore British-style hats to Downton Abbey events sponsored by our PBS station in Jacksonville, Florida. Each of our hats adorned with feathers, a flower and seed pearls cost $ 5.00 at Roots’ Country Market near Manheim, PA. We didn’t tell anyone at the gala how much our gorgeous hats cost.

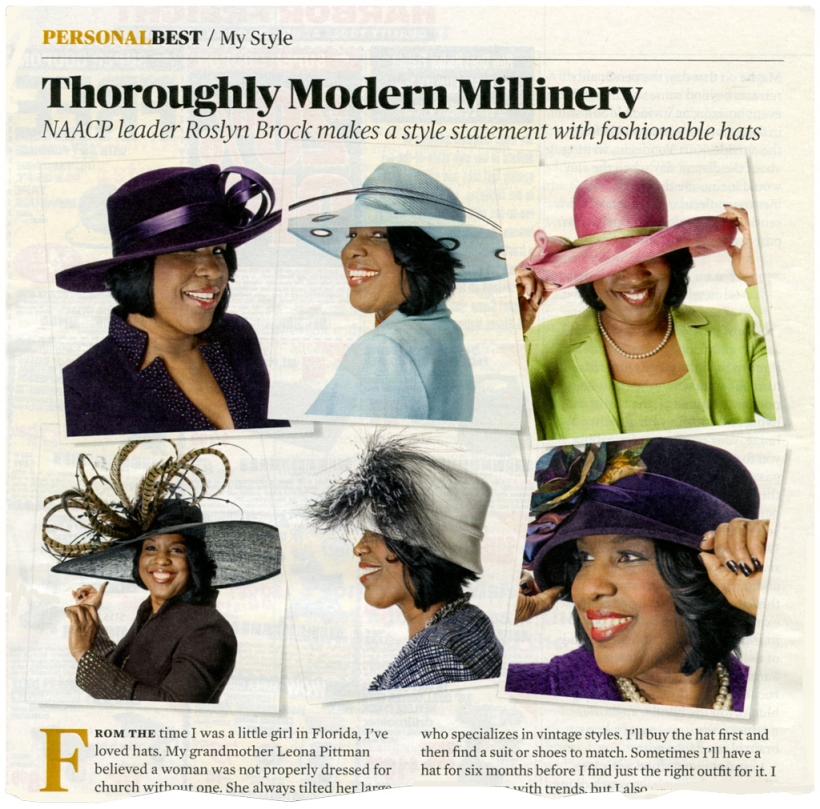

Hats have mostly gone out of fashion in recent decades, except among the trendy young. NAACP leader Roslyn Brock makes a style statement with her wardrobe of about 200 fashionable hats, expressing her love for her Grandmother Leona Pittman who “believed a woman was not properly dressed for church without one.” Brock emphasizes that

I’m following in the legacy of female civil rights leaders who completed their Sunday go-to-meeting clothes with fashionable hats.

Hats are the centerpiece of Roslyn’s wardrobe. She admits that she’ll buy the hat first and then find a matching suit or shoes. For Roslyn, who enjoys couture creations from Philip Treacy, Queen Elizabeth’s designer, wearing hats “keeps our history and culture alive.”

How a hat makes you feel is what a hat is all about. ~ Philip Treacy

In June it will be two years since my mother died unexpectedly. I still miss her terribly. Grief occasionally comes over me in waves. Now less often, with less severe impact. Still . . .

On my dresser I have kept three mementoes of Mother, one on top of the other: the two-quart Ball jar with bubbles in the glass, emblematic of her love of cooking and canning. And her last Mennonite black bonnet and white prayer covering veiling made of bobbinet fabric, a see-through, hexagonal mesh. Symbols of her constant faith and hope in God, each piece of headgear is less than half the size of those she wore in her youth.

Any hats in your history?

What did it look like? Where did you wear it? Do you still wear a hat? Comments are warmly welcomed. Don’t be shy.

Coming next: What Lights Your Fire?